At the Final OSI National Gathering on Unmarked Burials in Gatineau, Quebec, a panel presentation titled ‘Protecting the Ancestors’ sparked important discussions on how to address the protection of unmarked burial sites and the repatriation of respective cultural items and ancestral remains, including the children who never returned home from Canada’s Indian Residential Schools.

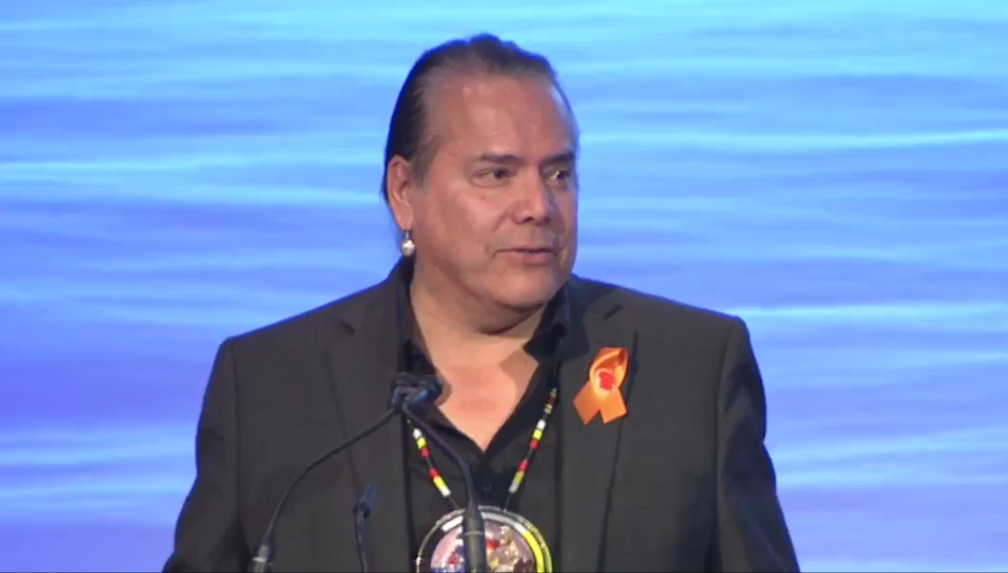

The presentation featured Grand Chief Garrison Settee of Manitoba Keewatinowi Okimakanak (MKO) and Councilor Melissa Hotain from the Sioux Valley Dakota Nation. They emphasized the call to protect and honour our ancestors, the work that lies ahead, and the importance of collective action in advancing these efforts.

"When they were young and going to school there was no one there to protect them, we have to protect them."

Grand Chief Garrison Settee of Manitoba Keewatinowi Okimakanak (MKO)

In this blog, we will explore the significance of the Protecting the Ancestors panel, the MKO’s efforts through the Path Forward Project, and the ongoing journey towards truth, justice, and accountability, as First Nations across Canada investigate unmarked burials associated with Indian Residential Schools.

During the presentation, several critical issues were identified that hinder progress in protecting unmarked burial sites and repatriating ancestral remains:

1. Lack of Federal Legislation: Canada currently lacks overarching federal laws that protect unmarked burial sites and facilitate the repatriation of cultural items. Without such legislation, these sacred sites are vulnerable to vandalism, neglect, and the potential erasure or denial of the children’s graves.

When human remains are uncovered on federal land or outside registered cemeteries, an investigation is generally required. Coroners, police, archaeologists and biological anthropologists are responsible for leading the investigation to determine the cause of death and to establish the legal and historical context of the discovery.

Federal jurisdiction over burial sites is limited, as property matters are generally governed by provincial or territorial laws. While federal bodies like Parks Canada and the Department of National Defense have specific policies for responding to archaeological discoveries, there is no single federal statute that governs burial sites.

Additionally, on November 5, 2020, Bill C-391, the Indigenous Human Remains and Cultural Property Repatriation Act, was introduced in the House of Commons. The bill sought to establish a legal framework for the repatriation of Indigenous human remains and cultural items taken without consent. However, it did not pass, leaving no protective measures in place for the remains or cultural items if they are discovered.

To access the Canadian Geographic map of unmarked burial sites associated with Indian Residential Schools, click here.

2. Private Land Ownership: Many burial sites associated with former Indian Residential School (IRS) sites are located on private lands, which presents significant challenges for their protection and the repatriation of cultural items.

Private land ownership complicates efforts to secure legal protection for unmarked graves, as landowners hold substantial control over the use and management of their property. For instance, the Sioux Valley Dakota Nation has been advocating for the protection of an unmarked burial site near the former Brandon Indian Residential School for over a decade. In 2012, the Nation offered to conduct a geophysical survey and provided evidence of a cemetery on the property, but the landowner declined to cooperate.

The site remained unprotected until 2018, when the landowner applied for a permit to redevelop the campsite. This led to the discovery of 56 potential unmarked burials, but despite the confirmation, camping restrictions were not enforced until 2021, after the public acknowledgment of unmarked burials at the Kamloops Residential School.

Even with this recognition, the Sioux Valley Dakota Nation continues to face resistance, as the landowner denied further access to the site in 2022, hindering efforts to continue searches and protect the burial sites. This complex problem between private land ownership and IRS burial places is anticipated to become more commonplace as more of these lands become subject to changing land use practices.

In 2023, The Sioux Valley Dakota Nation, along with the Manitoba Keewatinowi Okimakanak (MKO), urged the province to designate the cemetery as a provincial heritage site, pointing out the ongoing lack of legal protections for Indigenous burial sites.

To read more about the efforts of MKO and the Sioux Valley Dakota Nation, click here.

3. Provincial/Territorial and Municipal Laws: Provincial, territorial and municipal laws further add to the challenges, as they regulate cemeteries and burial grounds, often granting significant authority to provincial ministers, government officials, and landowners. Cemetery legislation in Canada primarily focuses on regulating the cemetery and funerary industries. Unregistered cemeteries or isolated human remains (not of recent forensic interest) often fall into a gray zone between regulations. Given that the vast majority of human history in Canada is Indigenous, many of these burial sites remain, unknown, unrecognized or unprotected under existing laws.

Approaches to managing these sites vary across provinces and territories. Protections are primarily driven by government agencies, and consultation with Indigenous communities is inconsistent, varying by jurisdiction and specific circumstances.

In Ontario, Indigenous burial grounds are granted specific protections once recognized or registered as cemeteries. This includes restrictions on site sales, transfers, and regulations for maintenance and public access. If human remains are uncovered outside registered cemeteries and a Coroner’s investigation determines there is no foul play apparent, the ministry responsible for cemeteries takes over the investigation with input from the ministry responsible for archaeology.

It is less clear how unmarked graves of children from Indian Residential schools get addressed. They are usually not registered as cemeteries and may or may not be treated as historic sites with protection under the Heritage Act.

While many former Indian Residential Schools across Canada have been designated as heritage sites, most legislation does allow for temporary ‘stop work orders’ to be issued if there is a risk of harm or damage to a site that could qualify for protection. Despite this, these designations do not guarantee full protection. Governments can still issue permits for alterations, sometimes for economic reasons, which means even sites with heritage status may remain vulnerable to desecration.

For list of Historic IRS Designation sites in Canada, click here.

4. Lack of Adequate and On-going Funding: Indigenous communities are taking on the crucial responsibility of investigating unmarked graves. While the government has provided funding for the first three years of investigations, the overall budget for investigations into unmarked burials was significantly reduced for the 2024-2025 fiscal year, falling short of what is needed for the scale of this work.

Protecting and maintaining Indian residential school sites, especially those with unmarked graves, requires substantial financial and logistical resources. Over the past three years, the Secretariat has only searched about 3.37% (20.5 acres) of the 600+ acres at the Mohawk Institute using ground-penetrating radar, lidar, and drone scanning.

Experts in archaeology, anthropology, and geophysics have highlighted that ground search efforts involve extensive data collection and analysis, which come with high associated costs. For example, drones can cost up to $17,000, with sensors around $20,000, while Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) systems cost about $40,000. ATV-mounted systems, while more efficient for covering larger areas, come with an even higher price tag.

Beyond the expense of purchasing, maintaining, and renewing this technology, the cost of expertise required to operate it and interpret the data can be even more significant. Additionally, these technologies come with a steep learning curve, requiring substantial investment in training and the development of local technical capacity. This process takes both time and money, further adding to the overall financial burden of conducting ground searches.

In addition to the equipment, there are hidden costs such as software, training, certifications, depreciation, data processing, and licensing. Currently, there are no widely established specialized training programs in Canada for these techniques, meaning Indigenous communities often rely on contracted partners for guidance. However, some initiatives are emerging to address this gap. The training programs offered in conjunction with Sioux Valley and through UBC Anthropology are notable exceptions, providing opportunities to build technical capacity. Other efforts are also underway, such as the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council funded project at the University of Alberta, which aims to strengthen local expertise and reduce reliance on external specialists.

Building the necessary capacity to complete this work will require long-term, collaborative partnerships and several years of effort. Without sufficient resources, even recognized sites may fall into neglect or disrepair, complicating the effort to investigate and preserve them.

Immediate Protection and a Path Forward

Currently, there is no cohesive, provincial and national strategy to protect former Indian Residential School (IRS) sites, unmarked burials, or to repatriate ancestral remains and cultural

items. During the OSI panel discussions, both Grand Chief Settee and Councilor Hotain called for immediate action to protect unmarked burial sites and proposed a comprehensive, four-step process to address this ongoing issue:

1. Immediate Protection: The first step is to protect unmarked burial sites from development and disturbance by temporarily designating them as heritage sites under the Heritage Resources Act. This would allow for immediate preservation of both public and private lands while ongoing care and custodianship are worked out. Amendments to the Act need to be made to ensure long-term protection and to create laws that align with Indigenous self-determination and rights.

2. Agreement Negotiations: The second step involves negotiating agreements with Indigenous Nations, governments, and stakeholders to ensure that Indigenous laws and customs are fully respected throughout the repatriation and protection process. This requires a co-development process, which upholds Indigenous self-determination and ensures that laws are implemented without limitations.

3. Acquiring Land: Step three calls on the provincial government to use powers under the Heritage Resources Act to acquire lands containing sacred burial sites without appeal, even through acquisition, and if necessary, while compensating landowners.

4. Transfer of Custody: The fourth step emphasizes the need for burial sites to be transferred into the custody of culturally affiliated First Nations, Metis or Inuit peoples to ensure ongoing care and protection.

A National Strategy

The panel also discussed a potential solution by proposing the creation of a policy similar to the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), enacted in the U.S. in 1990. This Act provides federal protections for Native American ancestral remains and cultural items on federal lands.

It was strongly emphasized that there is a need for a co-development process with Indigenous nations to develop and implement legislation similar to the NAGPRA Act. However, they were clear

that any Canadian version should not carry the same limitations as the NAGPRA program, which has faced criticism for inadequately supporting Indigenous peoples.

A central aspect of the recommendations made was to ensure that any new laws or amendments are rooted in Indigenous self-determination, giving Indigenous communities full control over the protection and management. The OSI panelists also emphasized the need for adequate funding from the Canadian government to support these efforts. It is not enough to pass symbolic laws; real, actionable change will require significant financial investment and commitment from all levels of government.

Indian Residential School burial sites carry deep cultural and emotional significance, representing the grief and trauma endured by many Survivors and their communities. For decades, these sacred sites have been improperly treated and left vulnerable to desecration, reflecting a denial of the dignity and value of Indigenous lives.

As a signatory to international agreements such as the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), Canada has a moral responsibility to align its federal and provincial legal framework to uphold its commitments to human rights and international law.

Implementing strong and enforceable laws to protect Indigenous burial sites, particularly those of missing and disappeared children, presents an opportunity to allow Indigenous communities to honour and protect the resting places of their loved ones. There is still much work to be done to rectify these historical wrongs and to ensure that the children are granted the dignity and respect that they deserve. To read more from OSI’s final report, click here.