The Survivors’ Secretariat has anchored its ground search work in a space of self-determination and intergenerational healing. As we work to bring the children home, we are also committed to uncovering, documenting, and sharing the truth about what happened at the Mohawk Institute to provide a sense of closure for the more than 60 communities whose children were taken to the institute.

With the former property spanning more than 600 acres and the legacy of the institute lasting 140+ years, the ongoing investigation draws on Survivor testimony, archival research, and the use of advanced ground search technologies to identify areas where unmarked burials may lie. From the beginning of our search, there has been no guidebook on how to do this work. Kamloops was the first site to use ground-penetrating radar in the search for unmarked burials at former Indian Residential Schools. Since then, communities across the country, including the Survivors’ Secretariat, have undertaken searches that build on that foundational work. From the very beginning, we sought wisdom from Survivors, Indigenous knowledge keepers, and experts in archaeology, geophysics, and mapping to help guide our way to develop a careful, respectful process rooted in truth.

“We began the search for unmarked burials at the Mohawk Institute, with a sacred purpose: to Bring the Children Home.”

Tony Bomberry, Survivors’ Secretariat Board Member Tweet

What has been clear to the Secretariat since the beginning is that the search must be guided by community, by history, and by Survivor testimony. Archives hold forgotten names and details; Survivors hold lived truths.

“I think of this not as research, but as a sacred and moral responsibility.”

Dr. Scott Hamilton Tweet

From the science of ground-penetrating radar to Survivors’ memories, the Secretariat examines both the strengths and limitations of the methods used in the search for missing children. In this blog, we share how this work unfolds, how the land is surveyed, what technologies are used, common misconceptions, and how Survivors, families, youth, and experts are walking this path together in pursuit of truth, healing, and justice.

How the Ground Search Works:

1. Creating a Strategy Involving Survivors, Intergenerational Youth and Technical Experts: Like many communities, when we started our search, we immediately purchased GPR equipment and began scanning the areas closest to the Mohawk Institute. However, we recognized that the capacity to conduct these searches was extremely limited and we sought to develop a strategy that trained intergenerational youth with the guidance of an archeological panel and with direction and support of Survivors.

2. Identifying Priority Areas and Relevant Historical Information: Survivors play a vital role in identifying areas where burials may have taken place, drawing on their memories and knowledge of known tragedies. Archival records, such as registers, maps, and reports, also offer important clues about possible cemetery locations and documented deaths. Additionally, historical aerial photographs, land use records, and topographic data are used to track changes in the landscape over time, helping to pinpoint areas that may hold unmarked graves.

3. Laying Out Search Grids: Once prioritized, areas are subdivided into 20×20 metre grids for precise scanning, with grid placement carefully planned to respect ecological and cultural concerns, i.e. avoiding tree roots, ceremonial spaces, and known grave sites. In the early stages, we relied heavily on police and forensic teams to lay out the grids for ground searches. Over time, however, our focus on building community capacity has grown significantly. Today, we’re able to lay our own grids using surveying and GIS technologies.

4. Ground Scanning: Multiple tools are used to scan each grid, building a layered picture of the subsurface. This requires complex tools and software including:

- Ground-Penetrating Radar (GPR): detects soil disruptions, i.e. rectangular shaped soil disturbance conducive of a grave shaft.

- Total Station and RTK Surveying: measure exact locations and elevations.

- LiDAR: captures high-resolution terrain changes, even under vegetation.

- Drones and Aerial Photogrammetry: create orthomosaic maps and 3D models.

The Survivors’ Secretariat is considering additional methods including the use of thermal imaging to identify temperature anomalies that may suggest past digging or disturbed soil as well as cadaver dogs to provide another level of verification of what they believe are potential burial areas.

“As of March 31, 2025, the Secretariat has scanned 567 grids — covering just 2.7% of the 607-acre grounds,”

Eric Patterson, Ground Search Lead Tweet

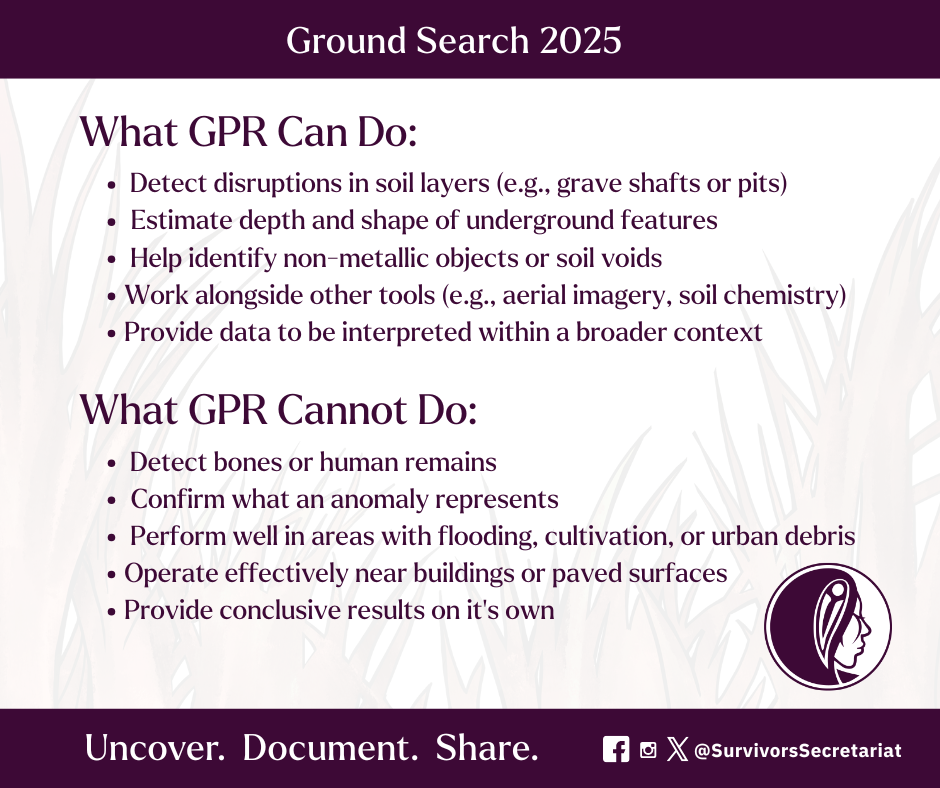

Understanding the Limits and Possibilities of GPR

Ground-penetrating radar (GPR) has become a symbol of unmarked burial searches in the public eye, but as Dr. Scott Hamilton emphasizes, it’s only one tool in a much broader toolkit.

GPR works by sending radar waves into the ground and reading the reflections. These reflections indicate changes in the soil, but they do not identify human remains. A signal could indicate a grave, or it could be an old latrine, a tree root, a storage pit, or the remains of a building. This is why a multi-technology approach coupled with Survivor testimony and archival research is necessary to ensure what we are seeing below the surface is indeed an unmarked grave.

Dr. Hamilton stresses the importance of a “toolbox” approach, combining GPR with magnetometry, electrical conductivity, soil analysis, and aerial photography, while grounding everything in Survivor testimony and historical records.

The data collected during these investigations also presents significant challenges, compounded by a shortage of qualified experts and limited resources. Data analysis remains resource-intensive and lacks standardized protocols. Despite advances in technology, the sheer volume of data requires detailed, line-by-line human interpretation.

Challenges Beyond the Technology

Technology is only part of the story. The ground search faces seasonal weather limits, difficult terrain, and layers of buried infrastructure and history, from 19th-century outhouse pits to 20th-century farming and development. At the Mohawk Institute, flooding from the Grand River and years of land alteration have made it even more difficult to read the soil clearly.

Technical challenges are only one layer. This work unfolds in the context of trauma, silence, and denialism. Access to church and government records remains uneven. Legal, financial, and bureaucratic barriers have also slowed down the work. And at every step, Survivors are asked to revisit painful memories.

“This work also demands something more intangible: trust. Survivors must feel safe to open the lid on memories that carry deep pain and trauma. When they do, their truths must lead.”

Laura Arndt, Secretariat Lead, Survivors’ Secretariat Tweet

As a not-for-profit organization led by Survivors and their descendants, the Secretariat must continue to navigate legal frameworks, financial constraints, and gaps in documentation, all while holding space for the truth, grief, and ceremony that this work demands. Despite these challenges, we remain committed to our mission: to Bring the Children Home.

Building Community Capacity (YSSP Ground Search Team):

Each summer, a dedicated team of Indigenous youth come together to carry out the sacred work of ground searches at the former Mohawk Institute. These team members are not only contributing technical skills, they are also taking part in a living history; their footsteps reclaim space. Their efforts restore dignity, and their work contributes to a larger movement of truth-telling and accountability.

The 2025 Ground Search Youth Summer Student Program (YSSP) brings together returning students along with new field workers from Six Nations and other communities impacted by the Mohawk Institute. From the start, youth have been central to this work as hands-on participants help carry forward the sacred responsibility of honouring Survivors truths.

“The youth that are involved, they’re not just students doing a placement. They’re carrying this work. They’re bringing their families' stories into it, and they’re supporting Survivors in a really beautiful, respectful way.”

Laura Arndt, Secretariat Lead, Survivors’ Secretariat Tweet

A Day in the Life of a Ground Search Team Member

Their days begin early, with a morning debrief to check in on mental wellness and prepare for the emotional and physical demands ahead. The team is divided into small groups of three to four members. Using measuring tapes and plastic pegs, they carefully set up grids on the land, respecting cultural and ecological sensitivities. Detailed field notes are recorded, capturing coordinates, ground conditions, and operational checklists.

Specialized equipment like GPR is then used to scan the soil for disturbances that might indicate unmarked burials. The process demands patience, precision, and teamwork. Each machine costs upwards of $50,000 per unit. Search areas are divided into 20×20 metre grids. One axis of the grid is scanned 80 times, 25 cm apart, and then the second axis is scanned using the same method. Each grid receives 160 passes with a GPR machine. Further complicating the process, the search day can be affected by weather conditions such as rain, humidity, extreme heat, or poor air quality.

“This work can harm our minds if we’re not careful,” reflects Chole, a first-year team member. “I’ve learned how important it is to use our traditional medicines to protect ourselves and stay spiritually grounded. Our medicine helps us carry this work and ourselves forward.” This balance of emotional care and cultural wellness is central to the team’s ability to navigate the weight of this important work.

Angelina Bomberry, the GPR team lead, shares that “The work can be emotionally tolling, but I’m determined to keep going. What gives me strength is working with other determined Indigenous youth who are just as committed. Our collective determination brings me hope.”

The Secretariat is honoured to work with such dedicated youth in the 2025 search season: Taka Thompson, Sophia Bomberry, Saka Thompson, Melody Courchene, Cloe VanEvery, Cameron Hill, Angelina Bomberry, and Alysa Whitlow — who approach the work with the care and respect it deserves.

Please stay tuned to our Facebook page this August to meet each member of this season’s YSSP Ground Search team.

Truth Can’t Be Rushed: The Search Continues

This summer’s ground search almost didn’t happen. As federal funding to the Indian Residential School Community Support Fund has seen significant cuts since 2024. This year’s ground search efforts would not have been possible without the support of Six Nations Health Services. This act of solidarity highlights the deep commitment Indigenous communities continue to express in the face of institutional neglect and funding shortfalls. Indigenous communities should not be left to shoulder the financial burden.

The Survivors’ Secretariat continues to call for sustained federal support. When the search began, experts estimated it would take up to ten years to complete, even with steady funding. This work is long, complex, and emotionally heavy, and it cannot be rushed.

We ask for patience. For respect. For an understanding that this is not just research — it is the work of bringing the children home. Let us follow the pace of Survivors and their communities, not the demand for quick answers. The Secretariat would like to thank all of our supporters for walking this path with us.